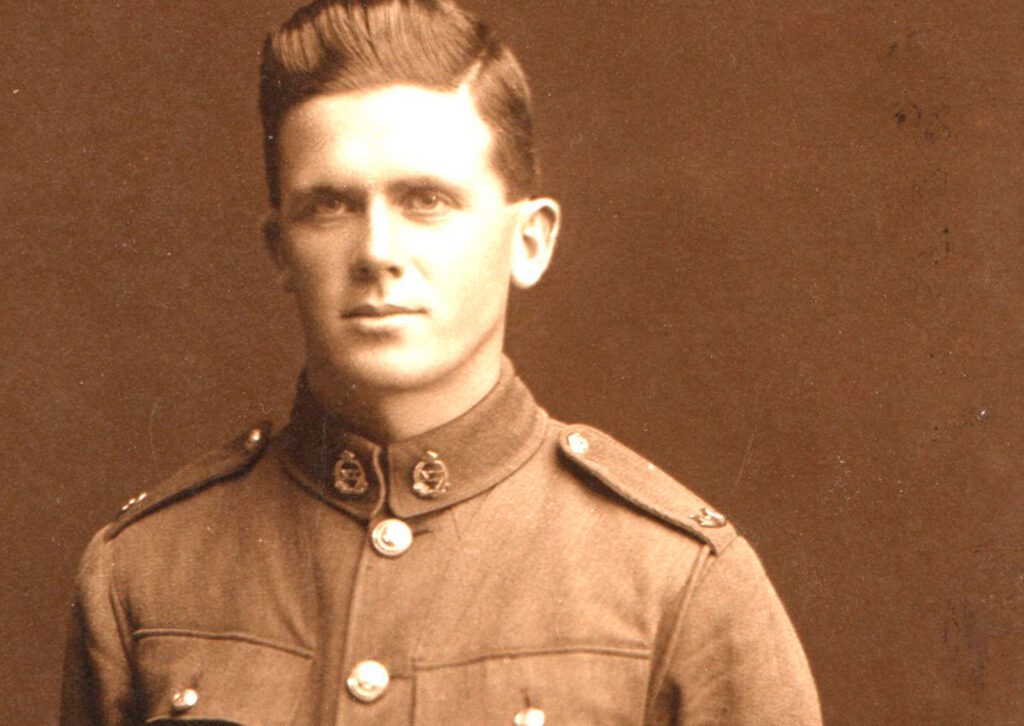

Le 4 novembre, jour de la libération, une journée spéciale de commémorations pour la famille d’un soldat néo-zélandais.

En matière de noms, difficile de trouver plus spectaculaire que Melbourne Ascot Inkster.

Les parents du soldat néo-zélandais, James et Eliza, l’ont nommé ainsi en hommage à la ferme d’Ascotvale, à Melbourne, où ils ont vécu avant de déménager à ‘Te Rauamoa’ Te Awamutu, où il est né le 31 décembre 1896.

Avant de s’engager pour la Première Guerre mondiale en 1917, Melbourne travaillait comme employé de bureau chez Spedding Ltd Importers.

« Son patron de l’époque,” raconte Kate Brooks, son arrière-petite-fille, “a déclaré qu’il était hors de question de l’appeler ‘Melbourne’ à travers le bureau, alors il l’a surnommé Peter. On l’a connu sous le nom de Peter quasiment tout le reste de sa vie. »

« Certains de ses cousins l’appelaient Melbie,” ajoute Kate, « et nous pensons que ce n’est pas si grave qu’il n’ait jamais vraiment été appelé Melbourne car cela nous a offert une histoire de famille qui se transmet de génération en génération. »

Se souvenir du Jour de la Libération

Le 4 novembre 1918, jour où les soldats néo-zélandais ont libéré la ville du Quesnoy à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale, est une journée spéciale de commémorations pour la famille de Melbourne, y compris Kate, sa mère Stephanie, sa tante Meredith, et Vivienne, la fille de Melbourne.

Même s’ils se trouvent à 18 000 km du Quesnoy, et que cela s’est passé il y a 106 ans, ils se souviennent de la libération parce que Melbourne a été l’un des chanceux à rentrer chez lui.

Melbourne faisait partie du 1er Bataillon de la Brigade de Fusiliers Néo-Zélandais et a été blessé à la tête au Quesnoy le matin du 4 novembre. Il est rentré en Nouvelle-Zélande où il a vécu jusqu’à plus de 70 ans.

« Beaucoup n’ont pas eu cette chance,” dit Kate, qui a visité Le Quesnoy et Te Arawhata cette année pour honorer son arrière-grand-père et rendre hommage aux soldats néo-zélandais tombés sur le Front occidental. »

« Nous pensons au 4 novembre en nous rappelant que même si Melbourne a été blessé par balle et a passé plusieurs mois à l’hôpital, il a pu rentrer chez lui. Tant de garçons ne sont jamais revenus. »

L’influent docteur māori, politicien et anthropologue, Peter Buck Te Rangi Hīroa, membre du Bataillon des Pionniers pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, a joué un rôle déterminant pour sauver Melbourne ce jour-là.

« Apparemment, les brancardiers allaient l’abandonner parce qu’il avait été blessé à la tête et semblait au-delà de toute aide. Mais Peter Buck a dit : ‘Non, tant qu’il y a de la vie, il y a de l’espoir’ et il a demandé qu’on le transporte dans une tente médicale. »

Cartes postales du monde entier

Melbourne a grandi sur la côte nord d’Auckland et partageait une passion pour la voile avec son frère aîné Jim. Après s’être engagé, quittant alors son emploi chez Spedding Ltd Importers, il est parti le 9 mai 1918 à bord du Maunganui, en direction de Liverpool via le canal de Panama.

Il collectionnait des cartes postales presque partout où il allait – des salles de danse en Virginie, aux États-Unis, aux hôpitaux où il s’est rétabli après avoir été blessé.

« C’était un collectionneur et il a gardé un enregistrement visuel de tous les endroits qu’il a visités, ce qui nous a permis de tout relier, » explique Kate.

« Il y a un album complet de cartes postales où il a noté les dates, les lieux et ce qu’il faisait. Ils ont traversé le canal de Panama, se sont arrêtés en Virginie aux États-Unis et ont visité une salle de danse les 8 ou 9 juin. Ce sont des archives incroyables. »

Kate a entendu parler du Quesnoy pour la première fois en 2012 lorsque sa mère a acheté un livre pour enfants racontant l’histoire de la libération.

« Je savais, enfant, que Melbourne avait participé à la Première Guerre mondiale. Mais lorsque ma mère a trouvé ce livre, elle m’a dit qu’il avait été impliqué dans la libération de cette petite ville. »

Elle se souvient aussi que sa mère lui racontait comment, enfant, elle s’asseyait sur les genoux de son grand-père et il lui demandait alors si elle voulait toucher la “crête” sur sa tête, en référence à sa blessure par balle.

La vie en temps de paix

Peu après son retour en Nouvelle-Zélande, Melbourne a repris son travail chez Spedding Ltd où il a rencontré Hazel, l’arrière-grand-mère de Kate.

« Elle l’a probablement connu sous le nom de Peter, donc c’est à ce moment-là que le nom est resté, » dit-elle en souriant.

Ils se sont mariés en 1923 et ont vécu à Bayswater avant de déménager à Wellington en 1927, où Melbourne a d’abord travaillé pour Spedding puis monté sa propre entreprise d’importation.

« Apparemment, c’était un homme calme, réfléchi et méticuleux dans la tenue de ses registres. Il aimait lire, avait un esprit curieux et a été abonné au National Geographic des années 1930 jusqu’à sa mort [le 9 août 1972]. »

Elle pense qu’il ne parlait probablement pas de la guerre pour ne pas ennuyer ou accabler les gens.

« Je pense que c’était révélateur de sa nature, étant un homme de peu de mots. Mais il n’a pas trop porté le poids de la guerre, étant arrivé vers la fin du conflit. Il s’est proposé pour la Seconde Guerre mondiale, où il était sergent dans la Garde Nationale. »

Selon Kate, pouvoir raconter l’histoire de Melbourne lui a permis d’apprécier le travail effectué par sa tante Meredith et sa mère, qui ont pris soin de conserver les histoires de famille.

« J’ai toujours aimé l’histoire et je suis une passionnée. Il y a quelque chose de spécial à connecter votre famille à l’Histoire. Voir les photos de Melbourne, comme lors de son passage par le canal de Panama… C’est incroyable que ces photos existent encore. Cela m’a donné envie de continuer cette transmission pour les générations à venir. »