Jim McKenzie’s wartime diaries and letters detail everything from life in the trenches to the glamour of Paris.

February 3, 1918

Dear Margaret,

I have reached the Mecca of all soldiers, the front line. Our home is about 30 feet underground in a tunnel.

I had a packet of sweets from you a couple of weeks ago and the tin of chocolates came to hand when I was up in the trenches … & my word I did hoe into the chocolates I can tell you.

So wrote Private Jim McKenzie to his sister Margaret while he was holed up on the Western Front “somewhere in France”. It is one of the hundreds of letters and diary excerpts painstakingly documented by Jim’s grandson Alan Hughes.

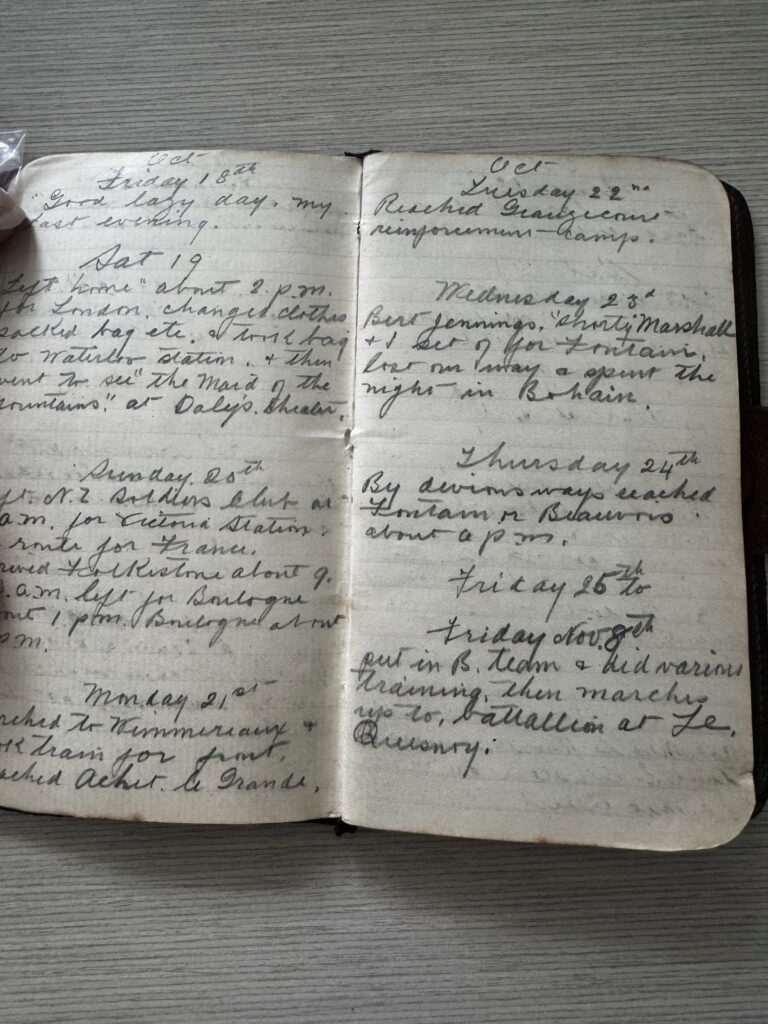

“With a magnifying glass, you’re figuring out what a word means,” says Alan of the process of reading and transcribing his grandfather’s diaries. “It wasn’t like how we speak these days or even write these days — it’s from another time.”

Alan received Jim’s diaries, letters, and memorabilia in the 1980s after his grandmother, Alice, died. He started transcribing Jim’s diaries in 1987 which make up the main content of his book, The Great Adventure.

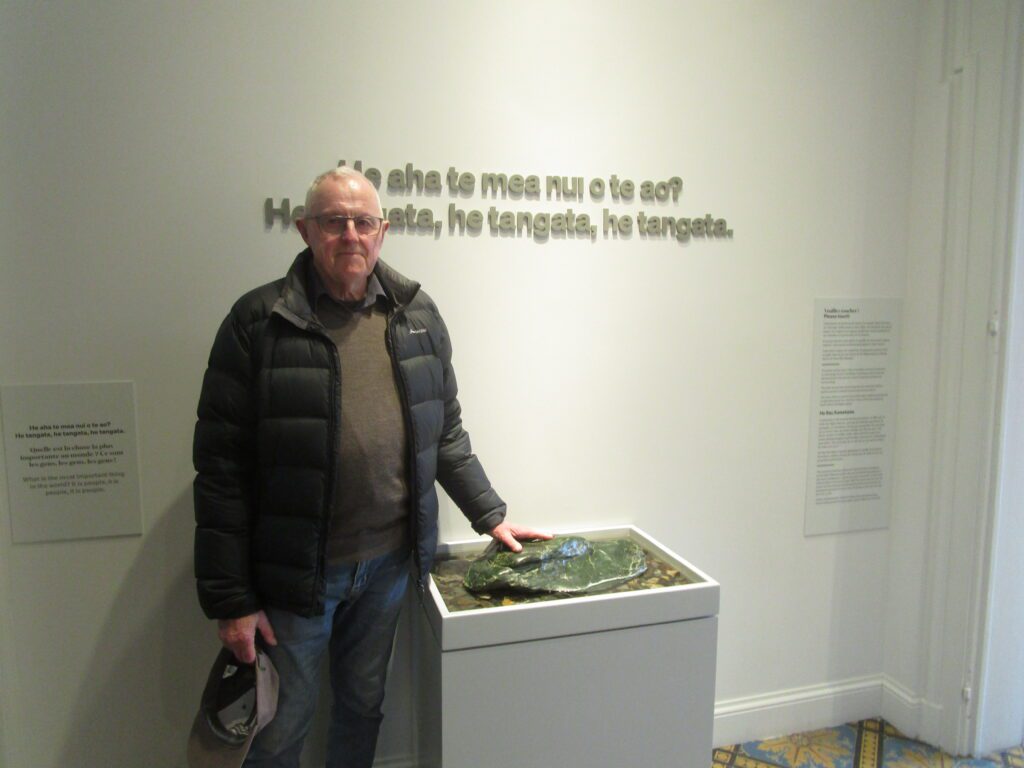

“Since then, I’ve produced three editions of Jim’s story,” says Alan whose role of Manager, Central Region at the National Library meant he had access to regimental history to provide context to Jim’s diary notes.

He laughs about how Jim’s diaries were often understated and brief, covering entire battles in one sentence or writing “ditto” for days on end, signalling the periods of monotony soldiers endured. Alan also wove extracts by historian Ormond Burton and the vivid and lively diary entries of Private Monty Ingram through Jim’s story.

“The Great Adventure is about keeping the memory of my grandfather alive,” he says.

In late 2024 Alan and his partner Eileen also visited locations on the Western Front, including a stop at the NZ Liberation Museum – Te Arawhata in Le Quesnoy where Jim was involved in the liberation of the town on November 4, 1918.

“I wanted to imagine what it might have been like for him 100 years ago. I wanted to imagine this gentle farmer from North Auckland with a bayonet in his hand, face to face with a German soldier,” recalls Alan.

“It was pretty challenging, but I wanted to experience it as much as I could.”

A musician, dancer, farmer and soldier

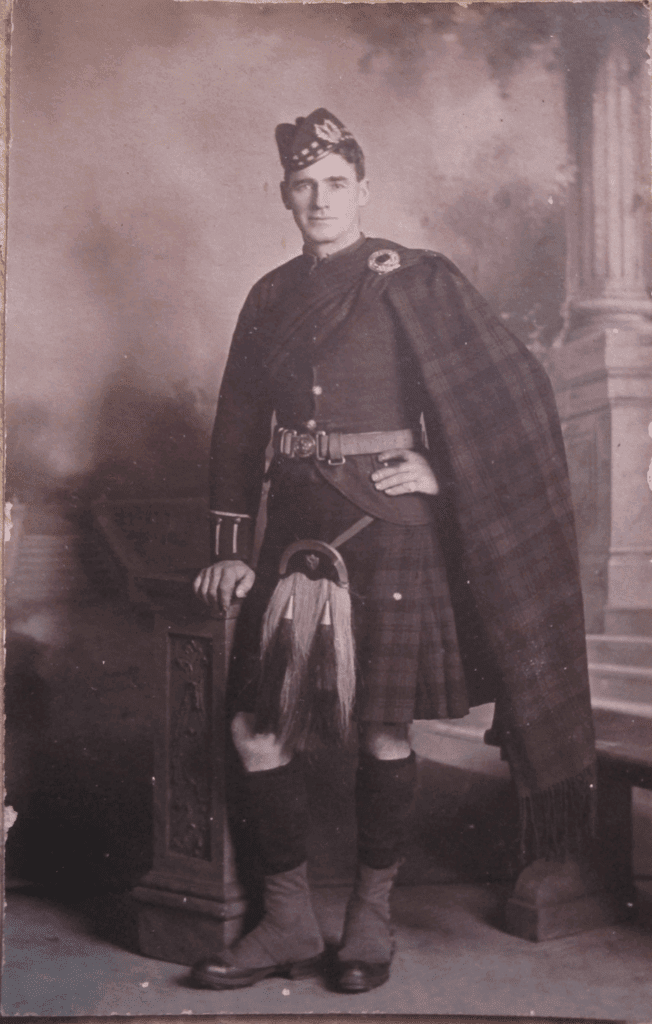

Jim McKenzie was born on 17 May 1876 in Russell, in the Bay of Islands, as the second youngest of James McKenzie and Jessie McDonald’s 13 children.

He started farming in Ōkaihau, a small town just north of Kaikohe in the Far North, and was known for being sociable, funny, and a gentleman with a talent for storytelling, music, and dancing. Along with his brother Bill he played violin in a local orchestra.

“He loved dancing, he loved conversation. He was typical of those Scots who emigrated: sociable, musical, family oriented,” says Alan.

Jim was 40 years old when he enlisted, making him much older than most soldiers. He lost sight in one eye in a forestry accident and was initially rejected for war time service.

“The family folk lore goes he memorised the eye chart,” smiles Alan, “and the medical papers say ‘sight of left eye bad’ but in fact he had no sight.”

Alan says Jim was also very determined to get to the war because his close friend Jack Bindon had been killed at Gallipoli.

“He loved singing and dancing and family life, and yet there he was, forced into a kill-or-be-killed situation.”

While away, Jim was a prolific letter writer, sending regular correspondence to his many siblings, his parents, and other relatives. His flood of correspondence started on his way to Europe when he sent postcards from stopovers in Cape Town, South Africa, and Freetown in Sierra Leone.

Jim arrived in Plymouth on Wednesday, 15 August 1917.

The road to Le Quesnoy

October 30, 1918 [Uncensored letter to Margaret]

Well, the war news is very good now, we heard today that Austria has chucked it in, if so, I guess Germany won’t last long, & we are sincerely hoping we won’t see any more fighting. I think we’ll all go just about crazy when the time comes to turn homewards.

Of course, there was one last battle to fight for Jim as he headed to Le Quesnoy. Jim’s company was charged with undertaking a clockwise flanking manoeuvre around the north of the town, storming the locations of Ramponeau and Villereau.

As Ormond Burton recounted:

“It was now obvious that the end was very near. Bulgaria surrendered. Turkey collapsed utterly. Austria was granted an armistice that amounted to practically unconditional surrender. The whole of the German Western front was crumbling rapidly.

In the meantime, however, there was the one more fight. Le Quesnoy, once one of the most important of the French border fortresses, was the objective of the Division. With the railway line passing through, it was still of very great importance, and was strongly held by the enemy.

After a miserable night, the morning of November 4th broke fair and fine.”

Private Monty Ingram continues:

“Suddenly the air is rent with the deafening thunder of artillery drumfire. The hour has struck! Popping of Vickers! Barking of field guns! Booming of heavies! Flashes in the greying dawn! Black smoke, red smoke, white smoke! Leaping earth, flying clods, and ripping steel! A tension of muscles and the first wave is off.”

Following the liberation of Le Quesnoy, Jim resumed his diary entries on November 9 with a simple: “Scouting round for vegetables.”

The great march

From November 11 and into December he writes about marching with “sore feet” as he and his regiment head towards Germany.

“At 42, he managed to keep up with the young fellows — they marched 150 miles into Germany,” says Alan.

In a postcard to his father on December 6, 1918, Jim writes:

Dear Dad

We have now done 6 days of the great march to the Rhine & I believe we do 6 more. However, I’ll be writing all about it later on. How does the peace negotiations strike you over there?

Your loving son, Jim

On Saturday 21 December 1918 at 7.45am Jim and his regiment finally crossed the German border.

Dear Margaret

Well my dear here we are at last in Germany after 16 days marching & no one is sorry that it is finished. We crossed the famous Rhine at 5.45 p.m. Sat 21st. That day we did about 22 miles & arrived here at 12 midnight. I am expecting those parcels soon, no xmas parcel to hand yet, but I hear there is a big one in. Will say au revoir writing soon.

Your affectionate brother, Jim

Settling for an extended period in the town of Immigrath, between Dusseldorf and Cologne, Jim combined mundane mess duties with making the most of being in a new country.

He had a flair for languages, and being billeted with families in Germany meant he picked up a lot of German. He also spoke Gaelic and some Te Reo Māori and included snippets of Māori in his letters home. He learnt Te Reo from friend Jimmy Kingi who was a worker on the family farm.

In Germany he travelled to nearby Bonn with his mate Jack Hipwell to visit Beethoven’s house and hopped across the border into Belgium to explore Liege. “The famous place the Germans first started the war,” he wrote in a letter to his nephew Huia.

But it was ice skating on the frozen lakes and ponds of Immigrath that got Jim most excited in the depths of winter in 1919.

“There are some good ponds near here and we have started skating, some fun, I was pretty awkward at first, but am improving,” he recounted to his brother Bill.

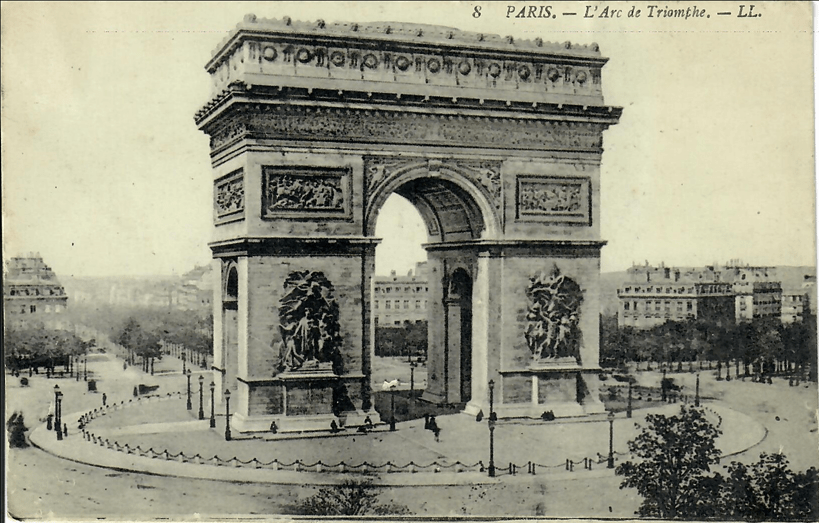

On February 12 he boarded the Paris Express bound for the City of Light visiting the Arc de Triomphe (“Built by Napoleon”), the Louvre, and, of course, the Eiffel Tower.

“Oh my, Paris is a great place,” he wrote to Margaret.

Jim returned to Germany for a short stint, then transferred to London at the beginning of March and spent the next two months travelling throughout England and Scotland. On May 10 he embarked for New Zealand, heading home through the Panama Canal and arriving in Auckland on June 23.

Return to the Far North

After returning to New Zealand in 1919, Jim returned to the farm in Ōkaihau, married Alice White (the “girl next door” who was 23 years younger), and had four children – Florence Joan (known as Joan, Alan’s mother), Margaret Anne (known as Anne), Gordon Cameron (known as Jock) and James Douglas (known as Doug).

Alan, his siblings, and cousins used to go to the farm during school holidays. Jim rarely spoke about the war, despite his grandchildren asking cheeky questions.

“We were kids and we’d rifle through drawers in the living room of the farmhouse and found a dagger. We’d say, ‘How many Germans did you kill with this dagger?’ — and he wouldn’t answer. His memory was fading by then.”

Alan was almost 10 when his grandfather died on 24 January 1958.

“My interaction with him was a 9-year-old boy meets an 81-year-old man. But he was quite a character, and I remember him as a lovely, funny old man who wore trousers with braces and smelled of honey.”