Tracing the Tapsell family connection to the Western Front – and beyond

Eremia Tapsell has a rich and colourful whakapapa that was sparked by a Danish chap called Hans Falk.

“Hans, who was born in Copenhagen in 1777, was a sailor and wanted to join the British Navy,” says Eremia.

“But with a name like Falk, and the fact Denmark and England were at war, that wasn’t going to happen. So, he changed his name to Phillip Tapsell to enable him to work on British ships.”

Phillip, as he was now known, sailed on a British whaling boat to the South Pacific and eventually settled in New Zealand in the coastal settlement of Maketū in Bay of Plenty.

“Phillip’s life was a crazy story of ups and downs, and the large Tapsell family in New Zealand today traces their Pākeha roots back to him,” says Eremia of the Tapsells, which includes Phillips’ great-grandson, the late Sir Peter Tapsell, a well-known MP and former Speaker of the House.

Phillip is recognised as having had the first Christian wedding in New Zealand and the first registered between a Māori and a Pākeha, when he married Maria Ringa of Ngāpuhi in 1823.

“The legend goes,” says Eremia, “that it lasted less than 24 hours – his young Māori wife running away in the night, never to be seen by Phillip again.”

Eremia recalls these stories following a trip to the Western Front where other members of his large family fought during World War One.

Remembering whānau on the Western Front

Eremia’s great-grandfather’s brother, Robert Tapsell, died during the Battle of the Somme and is buried in a Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery near Flers in France.

“Seeing your surname on a gravestone over there and knowing he was just 27, a Māori boy so far from his home in Maketū, is hard to fathom really.”

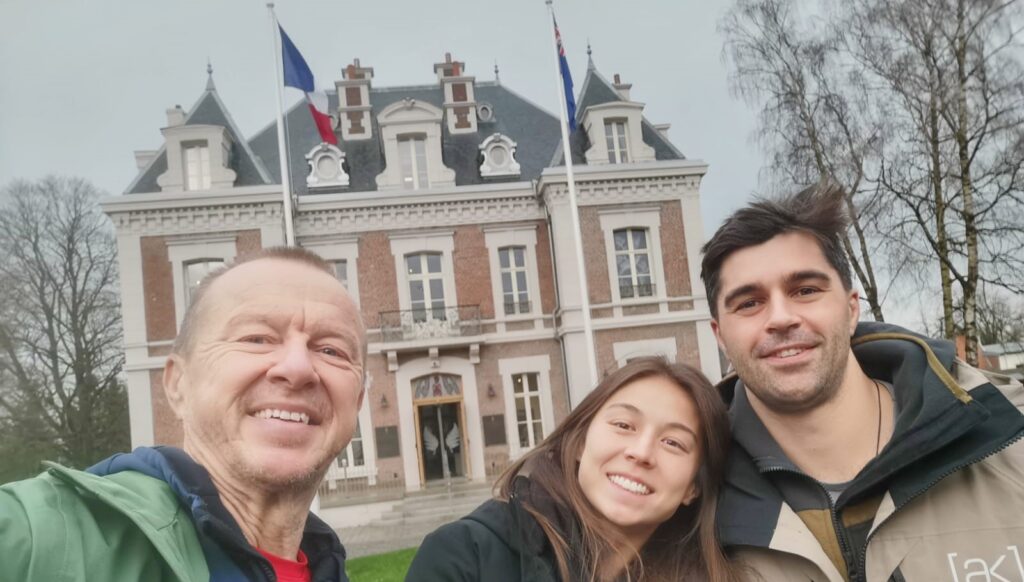

Eremia, along with his partner Sofie, who plays professional rugby in Lille, and her German father Ludwig, also visited the French town of Le Quesnoy where his Grandfather’s first cousin, Winiata Tapsell, played a key, and slightly mischievous, role in the liberation of the town.

Winiata was a member of the Māori Pioneer Battalion which was involved in the surrounding, and eventual capture, of Le Quesnoy on November 4, 1918.

The story goes that the Germans had blown up a bridge near Le Quesnoy’s Valenciennes Gate. Winiata, who regiment was tasked with supportive rather than aggressive movements, found himself out of position before bravely crossing the moat using a wooden plank and becoming the first New Zealander to make it within the walls of the town.

Tapsell never received any decoration for his actions, and was instead punished for being away from his post.

“It sounds to me like he wasn’t doing it recklessly. He obviously saw an opportunity to do his bit and go in with the reconnaissance.”

“But the more I read about that period, and especially the dynamic between the British Army and the New Zealand and colonial troops, you realise that his actions would have been out of line back then.

“It is sad he didn’t get any recognition for it, and again, the more I learned about that time, it’s likely there was a racial aspect to it.”

Although Robert was Winiata’s uncle, they were around the same age.

“When we visited Robert’s grave, there was sideways rain, it was super windy, and cold. There was no map of the cemetery, so we all split up, each of us took a section, and looked at each of the stones until we found it.

“Being there gave you a small sense of what sitting in a trench over 100 years ago would have been like,” says Eremia.

Maketū will always be home

Eremia’s father, Warwick, passed away in 2016. He shared a lot about his family’s history and Eremia’s mother, Annette, is also a wealth of knowledge about the wider whānau.

“There’s a big push amongst our family to keep the memories of our tupuna alive,” he reflects.

“A few of the Tapsell whanau have been to Copenhagen to see the street where Phillip Tapsell grew up and the church he was baptised in – to try to keep those memories alive,” he says.

But it’s Maketū that remains at the heart of the Tapsell family. Eremia, who is currently based in Dubai, goes back to the small settlement every time he returns to New Zealand.

“My brother has taken over the family farm. It’s no longer a dairy farm, but there’s kiwifruit and a bit of beef. I love going back and my dad is buried in the urupā in Maketū – the same one where Winiata is buried.”

This sparks stories about his great-grandfather, Kiri Rotohiko Tapsell, and his great, great -grandfather, Reti Reti (Retreat) Tapsell (Phillip’s son).

“Kiri married Pirihima Mokopāpaki from the Tauranga iwi, Ngāti Pūkenga, and the land our existing farm is on is from that marriage.”

He also recalls the story behind Retreat’s name: “In 1836, I think it was, Phillip Tapsell’s trading station was sacked and overrun by a war party from Ngāti Hauā [Matamata] that forced the family to retreat. First, they moved just down the road to Matatā, and then to Mokoia Island in the middle of Lake Rotorua. Retreat was born on Mokoia Island and named after this ‘retreat’ from Maketū.”

Visiting Le Quesnoy

There was much excitement when Eremia introduced himself to the receptionist at Te Arawhata using his famous last name.

“She smiled, ‘See if you can spot any of your relatives’. Then just like that, two seconds into the museum, that’s him. And then the lovely receptionist came running over, ‘Oh, that’s Winiata, that’s your relative.”

He was struck by the immersive nature of Te Arawhata’s storytelling and how it reveals the personal stories of the people involved in both the liberation and World War One.

“It is an incredibly emotional experience because it’s so immersive and puts you in their shoes back in that time.

“It obviously tells the story of Le Quesnoy and the liberation, but then it delves deeper into the people aspect of the story – where they came from in New Zealand and what their personal stories were.”

For Sofie, who is of Chinese and German descent, the museum was both deeply moving and informative. Her German father found the museum fascinating.

“His take on it is, ‘Thank you [Kiwis] for coming over and beating the bad Germans’. Because for a lot of German people it’s a difficult topic. But I think it’s important for Germans to come to a place like Te Arawhata because reflecting on that part of our history is something you have to do.”

Eremia: “Something I found incredibly interesting, and the museum highlights this so well, is how a lot of the soldiers at Le Quesnoy had been through all the major battles.

“They had started their training in Egypt, up to Turkey, and then battles like the Somme. Sadly, many didn’t survive, like Robert, but you forget that a lot of those soldiers who liberated Le Quesnoy went through four years of it. They would finish a battle, have a couple of days, and then get sent to their next one. It’s hard to imagine really.”