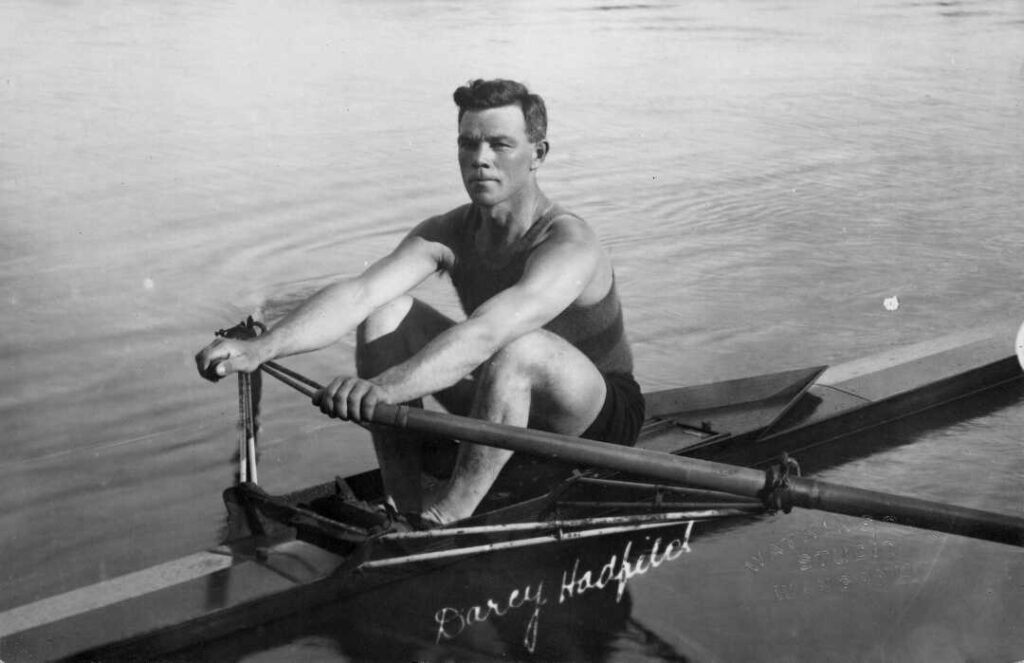

Olympic rower and WW1 soldier Darcy Hadfield was a tenacious competitor

Darcy Hadfield grew up in boats. Living in the secluded farming community of Awaroa Inlet in Tasman Bay during the late 1800s, there was no road access meaning boat was how he and his family got from A to B.

So, it was no surprise that rowing became a significant part of Darcy’s life – and paved the way for him to become one of New Zealand’s greatest scullers and an Olympian.

As a single sculler he won his first national title in 1913. He was renowned for being fiercely competitive, and in handicap events despite conceding a head start to other competitors he would still win.

This tenacious spirit did not waiver, even later in life. His son, Rex Hadfield, told the Bay of Plenty Times in 2011: “Dad was just an unbelievable competitor, even into his 60s. We’d have races from [Auckland’s] Waitemata clubhouse up [to] Okahu Bay and back. I’d go hard and he’d just go harder, and I never got past him.”

Darcy retained his national title in the single sculls in 1914 and 1915 before the championships went into recess due to the First World War.

He was one of many Kiwi athletes and Olympians who served in World War One including Harry Kerr, the first New Zealand-born Olympic medallist who won bronze in the 3500m walk in London. Kiwi tennis champion Anthony Wilding, who won eight Wimbledon titles and an Olympic bronze medal at 1912 Stockholm Olympics, was killed in action at the Battle of Ypres on May 9, 1915.

From rower to soldier

Darcy took up competitive rowing after moving to Auckland in 1911 aged 21. He worked as a shipwright (a term for a ship builder), including for a time with the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand, and joined the Waitemata Rowing Club during which time he won his three consecutive national titles.

On August 29, 1916, Darcy married Sarita. Soon after, he embarked on active service with the First Battalion Auckland Infantry Regiment.

In 1917 he was wounded in the head by shrapnel at Passchendaele. After recuperating in England, he returned to the Western Front only to suffer a bronchitis attack and was again sent to England to recover. During this second stint of recovery the war ended.

A golden era for sculling

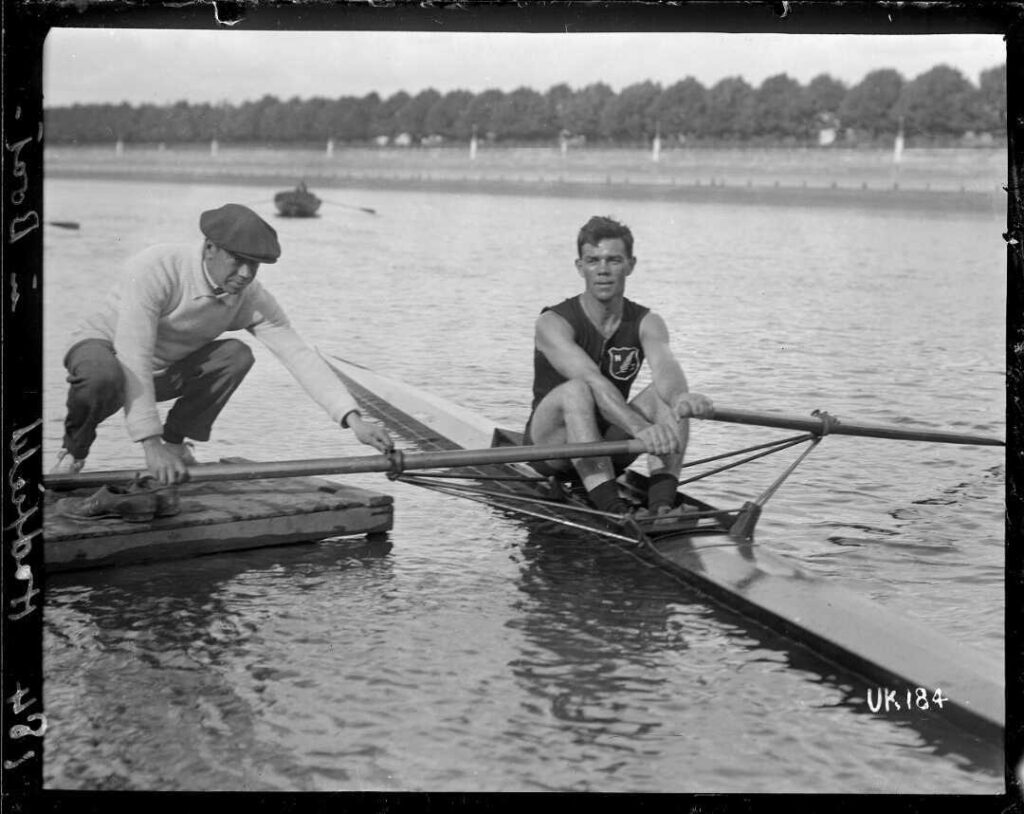

After the war, Darcy joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Rowing Club which held regattas to entertain troops who were demobilising after the war.

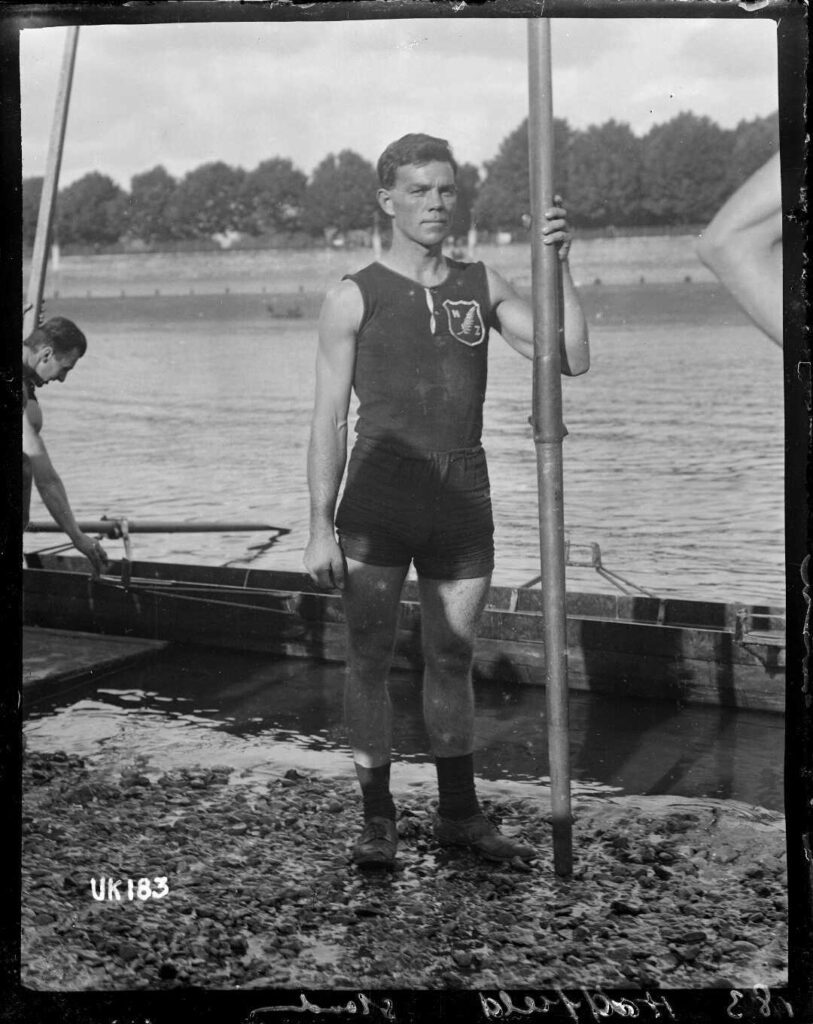

He remained unbeaten in single sculls in 1919 and at renowned rowing club Henley the same year he raced to victory in the Kingswood Cup, cheered on by New Zealand troops.

Darcy also triumphed in the Inter-Allied games in Paris where he was presented with a gold stopwatch by French war hero Marshal Phillipe Petain. The watch became one of Darcy’s prized possessions. The following year, Darcy went on to win a bronze medal in the 1920 Antwerp Olympics.

Two years after his podium at the Olympics, Darcy switched to professional rowing and challenged Dick Arnst for the world title. On the Whanganui River in front of 12,000 spectators, Darcy won by 10 lengths, earning 200 pounds.

However, his reign was short lived as Australian Jim Paddon lifted the crown three months later and also managed to hold off Darcy in the return match.

In 2011, Rowing New Zealand’s Richard Gee told the Bay of Plenty Times, the era Darcy was competing in was a golden time for sculling with rich prizemoney purses and large crowds cramming riverbanks around the world.

“This was the great era of sculling, we’re talking 1882 to about 1920, where they’d put two or three scullers on big rivers and let them fight it out,” he said.

“It isn’t overstating it to say [that] these guys [like] Darcy were like prize fighters. They were the heavyweight champions of the world – fully professional and internationally famous.”

Gee also recalled Darcy’s physical and technical abilities: “Physically [1.80m] Darcy wasn’t big by today’s standards, but he was all muscle and a beautiful technician, a blueprint for what we’ve got today. He was also rock hard, that’s what he was known for by the Brits and Americans.”

Darcy’s top class rowing career ended in 1923 but his passion for the sport lived on. He remained active as a coach, administrator, boat repairer and a veteran oarsman until he died in 1964.