Three of the Kean boys from Southland served in Europe during World War One but only two came home.

Private Denis Kean fought in Gallipoli and then, in 1916, was wounded at Ypres on the Western Front. After being wounded a second time at Passchendaele in 1917 he returned home to New Zealand.

Denis’s younger brother Private Jack Kean was wounded in the Somme and older brother, Rifleman Peter Kean, was wounded at Messines in 2017.

All three brothers are captured in a photo while on leave in London in June 1918 – the last time they would be together.

“They would have enjoyed meeting each other in London while on service leave. It would have been special,” says Peter’s great nephew Steve Tritt whose grandmother, Walterina Mary Kean (known as Lily), was Peter’s little sister.

“Jack was badly disfigured when he was shot in the face during the Somme advance. He returned home, married late in life at 50 and had two children. Sadly, Peter went back to the Front and was killed during the Liberation of Le Quesnoy on November 4, 1918.”

Peter’s story lives on thanks to Steve. He has documented Peter’s life during war time in a special story he has written for his children, grandchildren, and their children.

Peter’s story lives on thanks to Steve. He has documented Peter’s life during war time in a special story he has written for his children, grandchildren, and their children.

“Rifleman Peter Martin Kean never made it inside the ramparts [of Le Quesnoy] and never heard the cheering crowds,” writes Steve.

“He died outside the walls, on the day of the liberation. It is believed to be in front of the ramparts sometime after 9am. It is possible that he was seriously wounded and taken to an aid station, which might explain why he is buried at CWGC Cross Roads Cemetery, grave IF28, at Fontaine-au-Bois, which was a site chosen to gather up and concentrate the scattered dead from the small cemeteries and churchyards that mark the route of the final advance.”

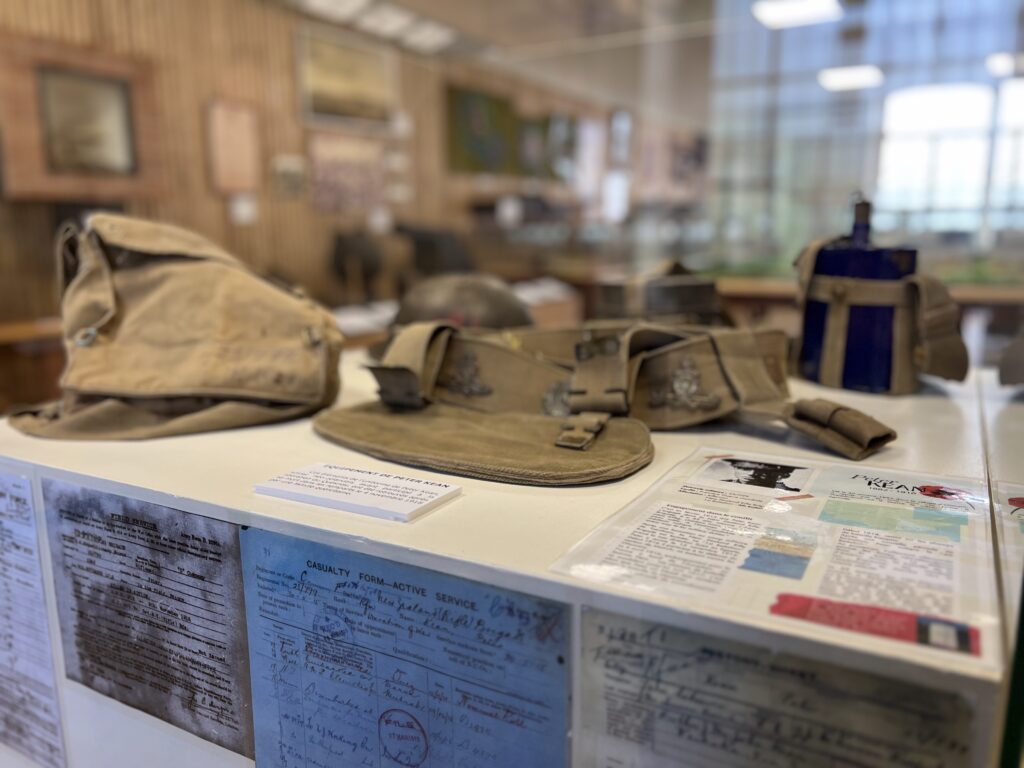

The telling of Peter’s story has also revealed an incredible connection to a Le Quesnoy local. The name Peter Kean was familiar to Te Arawhata Museum Director, Elizabeth Wratislav, after uniform items labelled with his name were displayed in a pop-up exhibition by the Le Quesnoy History Society.

The great grandfather of Le Quesnoy resident Christian Basuyau found the items including a drink bottle, D-shaped mess tin, webbing belt and gas mask bag labelled ‘23/799 P. Kean’. Today, Christian is the secretary of the Le Quesnoy history society and the items are displayed in an exhibition space at the Centre Lowendal (five minutes from Te Arawhata).

“How incredible, after more than 100 years, it is to see the items that Peter carried into battle and to know they are being well looked after, on display, and telling their own story,” says Steve.

“On their own they are remarkable, and with the family story added, it’s just unbelievable serendipity.”

For Christian the objects are much more than just military equipment. “They carry the memory of a man who came from far away to defend a land that was not his own,” he says.

“In their humble way, they also symbolise the bonds that unite people separated by thousands of kilometres but brought together by history. I like to think that it was this idea that inspired my great-grandfather when he found them at the end of the fighting.”

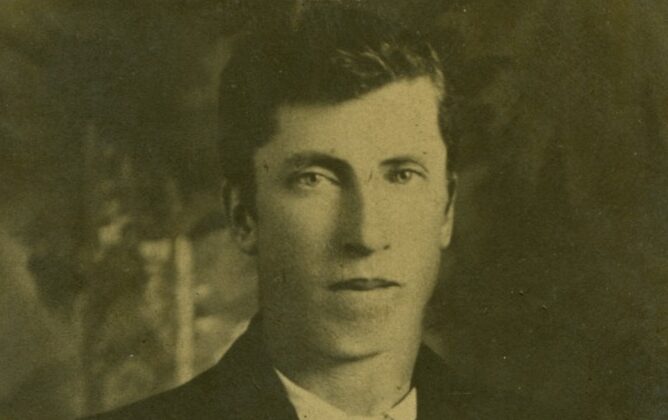

Peter was 37 when he died and posthumously received the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

Steve remembers the words of Private Bashford in Christopher Pugsley’s book: Le Quesnoy 1918 New Zealand’s Last Battle, where he said, “From the first days of war until the last, men will die, and to those concerned an equal misfortune, and yet there must be more sympathy for those who so nearly finish the course, but fall at the last fence.”

From Galway to Otaraia to Le Quesnoy

The Kean family has a rich Irish history. “In 1981 we attended a Kean family wedding in Gort, County Galway. It was fantastic to meet cousins and other relatives,” remembers Steve.

Peter and Lily’s dad, Denis Kean, was born in 1838 in County Galway and left in 1857 for the Australian Goldfields in Ballarat. When gold was found in New Zealand he was part of the Dunstan gold rush in 1862 and later worked the Shotover River and Gabriel’s Gully.

When land became available for settlement via the Deferred Payment Plan in 1875, Denis secured 200 acres and bought an adjoining 200 acres in Otaraia around 70km north-east of Invercargill.

Denis’s wife Maria Josephine Corcoran, who was also Irish, had thirteen children between 1878 and 1896 although sadly five died either at birth or were stillborn.

Peter was born on 30 October 1882 and was the second eldest. Maria died in 1896 aged 40 when Peter was just 14.

Following the death of his wife, Denis Snr and oldest daughter Margaret cared for 10-month-old Jack, Denis (two), Lily (three), Julia (five), Maria (10), and Kate (12). As a 14-year-old Peter worked with his father on the farm.

The family farm was sold in 1908 and Denis moved to Waikaka, also in Southland, where he died aged 72 in 1910.

Before the war, Peter worked as a farm labourer at Wedderburn Station, located on what is now known as the Central Otago Rail Trail. When he went to war, he was much older than traditional soldiers, says Steve.

“I’m not sure what motivated him. He wasn’t married so I can only assume, for him, it was an adventure like it was for so many.”

Peter, a Rifleman with the 1st Battalion N.Z.R.B., 7th Reinforcements, first saw action at Masah-Matruh on the Western Egyptian Front on Christmas Day in 1915. After heavy fighting with the New Zealand Division in the Armentieres sector and the Somme he was in good health.

However, on June 7, 1917, while taking part in the Messines battle, he was wounded in the right shoulder.

As Peter’s death notice in The Ensign on Monday 25 November 1918 documents:

“After spending some months [recuperating] in England, he returned to France and joined his comrades in helping to stem the German advance towards Amiens. He again took part in the British advance from Hebuterne and was present at the captures of Gommecourt, Cambrai, Bapaume, Serre and Prussieux Ridges.

“He finally was killed at Le Quesnoy on November 4 when that town was stormed and captured by the New Zealanders, this being the last battle in which the New Zealanders took part prior to the signing of the armistice with Germany.”

Sister city connection

“I knew about Le Quesnoy long before I knew that great uncle Peter fought in the liberation of the town,” says Steve.

His sister-in-law Cath Mitchell and her husband Warwick travelled with military historian Herb Farrant, the founder of the Trust behind the NZ Liberation Museum – Te Arawhata, on numerous tours to the Western Front battlefields including, Le Quesnoy.

Steve followed the progress of Farrant’s museum project and the conversion of an historic mansion house, which was the local gendarmerie headquarters, into Te Arawhata with a visitor experience by Wētā Workshop.

“It is a wonderful triumph of perseverance,” says Steve of the museum which opened in 2023 after Farrant first proposed the idea in 2000.

Steve also worked at Waipa District Council meaning he worked in Cambridge which is a sister town to Le Quesnoy.

Because of his family connection through Peter and working at council, Steve and his wife travelled to Le Quesnoy in 2018 for the centenary of the Liberation.

“We paid our way and went with the council delegation to the commemoration. It was a fantastic honour to be more than just a spectator especially because that deep family connection with Peter.”

Peter’s Le Quesnoy legacy lives on

“I loved walking through the town with everyone. It was surreal to be standing outside the walls, with the French and New Zealand officials, where Peter had died 100 years before.

That’s when I thought of Peter who died outside the walls, he didn’t make it into the city, and he did not celebrate with the locals.”

At the official dinner in Le Quesnoy on November 4, 2018 – which also happened to be Steve and his wife’s wedding anniversary – they remembered, and celebrated, by raising a glass of Champagne to Peter.

“Knowing Peter’s story gives a historic point of reference for my family, my kids and their kids. These days fewer people have a direct connection with the war, so keeping family stories alive is important.

“So documenting Peter’s story offers a personal connection with one of the world’s most significant events and hopefully means that family coming after, will know about it and remember it.”