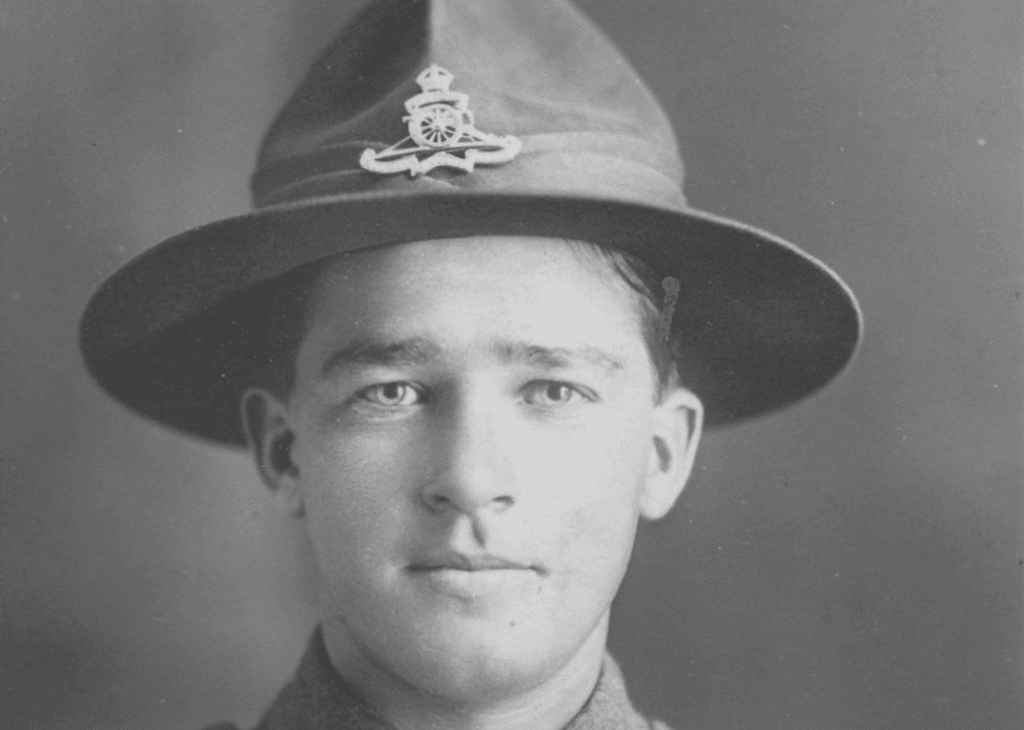

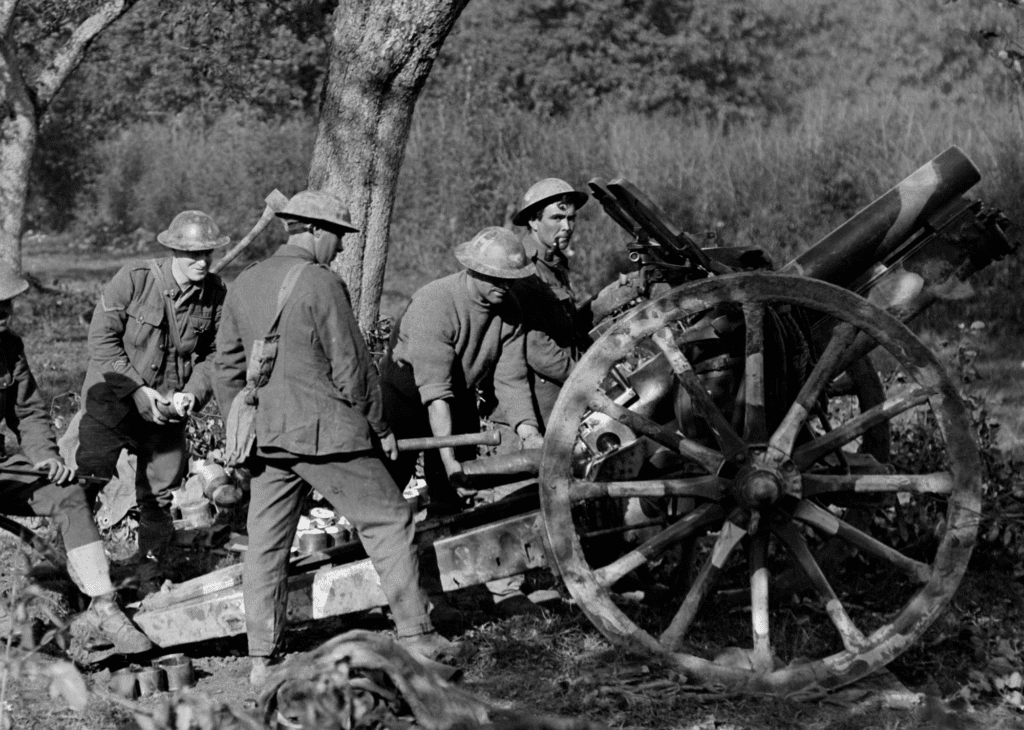

Iconic photo captures howitzer operator Geoffrey Challies in Le Quesnoy orchard

The family of Geoffrey Challies still have the pipe he puffed on while out in the battlefields of World War One.

Geoffrey – from the New Zealand Division, NZ Field Artillery – is captured in an iconic photo taken by New Zealand’s official war photographer Henry Armytage Sanders in an orchard just outside of the French town of Le Quesnoy.

He is eyeballing the camera, pipe in mouth, as he stands by the heavy-duty Howitzer cannon he helped to operate in the lead up to the liberation of the town on November 4, 1918.

“My brother Christopher has got all dad’s records. He’s got his pipe, the one that’s in the photograph,” says Geoffrey’s daughter Miriam Farrell.

“That’s him there,” she says holding a copy of the photo. “He signed up on his 20th birthday in October 1916. They couldn’t go before that. He left New Zealand early the following year. His older brother was already over there. That could have been a reason he was so keen to go.”

Sadly, Miriam passed away late 2024 following the interview. Her granddaughter, Gretel Donnelly, says she (Miriam) would be chuffed her father’s story is being told.

Miriam loved a delightfully deadpan letter Geoffrey wrote to his mother, Florence, in October 1917:

“I received my birthday cake today all in good order. I cut it a few minutes ago, so as to be able to tell you what it was like. Well, it arrived in first class order. I expect to go to France in 2 days time so I must hurry up and finish the cake before I go.”

“They weren’t allowed to write anything about the war so a lot of what he wrote was about things like him being excited to get his birthday cake, gingernuts and socks,” smiles Miriam.

Living in Le Quesnoy’s sister town

It wasn’t until Miriam and her husband Brian retired to live in Cambridge that they heard about the small French town of Le Quesnoy – and Miriam discovered her father’s connection to the liberation of 1918.

“We moved to Cambridge in 1996 and then in 2000, Cambridge became the sister town to Le Quesnoy. I rang my brother up, he’s older and I asked him, ‘What did Dad do during the First World War?’

“He reeled off this and that and of course, his involvement with Le Quesnoy came up, but I had never heard about it because he never mentioned it in his letters from the war.”

Miriam, who was 11 years old when her father died in 1953, says Geoffrey’s strong connection to Le Quesnoy inspired her to delve deeper into her father’s war time adventures. She and Brian have visited Le Quesnoy three times and are members of the Cambridge / Le Quesnoy Friendship Association.

“Kiwis are very much welcomed to Le Quensoy, it’s incredible,” she says of the town whose connection to New Zealand endures to this day with its annual Anzac Day commemorations and the NZ Liberation Museum – Te Arawhata.

Life on the Western Front

In a letter from September 1918, a month before Geoffrey was photographed in the Le Quesnoy orchard, he describes his transition from being a driver to operating a howitzer.

“I have given up my job as driver and have taken on gunnery. I think the gunner’s job is the best during the winter. It is not a very nice job looking after horses and harnesses during the winter when there is so much mud.”

Miriam’s husband, Brian, a military enthusiast, knows a thing or two about howitzers. He recounts how Geoffrey was “the layer” on the howitzer who was responsible for setting the sights and choosing the shell.

“They are monstrous things. Geoffrey is the one sitting on a special little seat on the howitzer known as the layer’s seat. The layer needs to have good mathematical nous to calculate the angle and how far you want the shell to go each time it is fired.

“They put the propellant in little bags and depending on what your target is, they have to calculate how many bags of this powder is needed to put behind the projectile.”

Brian says while the New Zealand Rifle Brigade played the key role in the liberation of Le Quesnoy, the NZ Field Artillery also played an essential part.

“They [the New Zealanders] were the only brigade available that were up to full muster. All the others, the English, the Canadians, and anyone else around there were all way down on numbers. So, Le Quesnoy was a totally New Zealand thing, and they incorporated Geoffrey and his mates from the artillery into the brigade to assist. It was a beautiful affair because everyone supported everyone else.”

Back home to life on the farm

After the war Geoffrey settled on the family farm in Mahakipawa in Pelorus Sound, around 45km northwest of Blenheim.

“Katherine Mansfield frequented the area because her cousin ran the guest house,” says Miriam of the famous New Zealand author.

While many New Zealand soldiers were offered land in the Marlborough Sounds as part of the soldier settlement scheme, Geoffrey’s parents had purchased their farm earlier.

“When Geoffrey and his brother, Ted, came home from the war, their parents bought the farm across the road,” says Miriam.

“It was a lovely farming valley between the Queen Charlotte and Pelorus sounds. The farms – little 100-acre blocks – were mainly settled by World War One soldiers, so there was a big group of them. They used to have a gun club and all sorts of things in those days.”

Miriam remembers her father being a successful farmer in what was one of the most beautiful parts of New Zealand.

“Because they had the two farms they farmed them together. We had mixed dairy and sheep. We had pigs, of course. There was a lovely big cheese factory, and the Marlborough Sounds right there on the doorstep.”

Geoffrey also built his mum a beautiful house on the farm, says Miriam. “He was a qualified builder and did business acumen and architecture courses in Cologne before leaving Europe after the war.”

The impact of war

Rain on the tin roof of the family home and muddy areas of the farm were constant reminders of Geoffrey’s time on the Western Front and caused anxiety attacks. “Mum said it used to really upset him,” recalls Miriam. “They didn’t know anything about PTSD at all back then. And it was very rare that anyone would come back not damaged in some way. It was very hard.”

Despite his anxiety, Miriam remembers her dad as a quiet, intelligent and practical man.

“He was still farming when he died. But because I was only 11 years when he passed away, so I was still fairly young, I learnt a lot about him from his war time letters. You can tell he was very caring and wanted to make sure that his family was okay. He would send them good, optimistic thoughts.”

In one of his last letters from the front, he pokes fun at his father having to deal with a mule called Kit.

“I am glad that Dad is getting on alright with Kit. You were saying that she is a bit lively at times. I think that is rather a good fault. I think Ted and I will be able to manage her alright when we get back, after some of the mules that we have had to handle at times.”

In another letter during his first year in service he tells his mother about meeting up with his brother, Ted:

“He is looking very fit and well. We are not camping very far apart at present, so we are able to see each other pretty often and generally manage to make a visit after each mail arrives so as to compare notes. I must close now with love to all from Geoff.”

“We’re just very proud of him for who he was,” says Miriam. “He was a very gentle, very kind man.”